what’s the deal with big fucking deal?

1 – CONCEPT

or WTF is BFD?

You have decided to go outside and talk to people you vaguely know, perhaps with the intention of “networking,” but most likely due to the prospect of free food/booze.

QUESTION ONE: Somebody with a good career, and possibly a similarly employed partner, who may even be responsible for multiple children, has just asked you what you do. How do you respond?

A) Tell them you are unemployed or in food service/retail, and hope they don’t judge you as much as you judge yourself.

B) Tell them your job is just “how you pay the rent,” and confess to making comic books.

QUESTION TWO: “Oh comics, do you mean like graphic novels?”

A) Yes, that is correct. I meant graphic novels.

B) Well, sort of, you see, I wouldn’t really call my work novelesque…

C) That’s a publishing term and not a medium, you idiot. Fuck off back to amateur hour.

QUESTION THREE: “What are they about?

A) Superheroes.

B) Oh shit.

It doesn’t matter how many articles have been published in the past 30 years about how comics “aren’t just for kids anymore,” or how many college courses assign Maus or Persepolis every semester, I often feel delusional, or at best ambitious yet wholly misguided, when describing non-Superhero comics to the unfamiliar:

“Well…it’s like…you know Ghost World? They did a movie…not a horror movie, no, it’s more…American Splendor? Paul Giamatti…No? Harvey Pekar, this guy who worked with R. Crumb, you know R. Crumb? Yeah, yeah, “keep on truckin’.” No, nothing like that though…It’s just about kids, hanging out, not really autobiographical, sort of though, I guess “literary,” but that sounds kinda highbrow, which, well…yeah, like Archie I guess, but…” All the while the voice in the back of my head is surging towards the front, telling me to shut up, they don’t care, they were being polite and now you’re making an ass of yourself jabbering away, this is Minnesota goddamnit, and you’ve been talking about yourself for more than two minutes, you are now officially “real different…”

The problem, I’ve come to realize, isn’t so much that the general public is unfamiliar with contemporary comics, it’s that I have no idea how to summarize my work. If I could quickly tell you what BFD is about, it wouldn’t be 250 pages long.

The phone rings – it’s Carl. Scotty answers. Lights go up on stage right, revealing CARL, surrounded by stacks of paper, sketchbooks; his laptop sprouting endless cables – an effective techno-cephalopod. His fingers are covered in ink, which he has unknowingly smeared on his face and t-shirt.

Carl: Hey dude, what’s up?

Scotty: Just trying to write that little process piece thing about BFD.

Carl: Cool. Finishing up layout. You think we should include a summary on the back of the book?

Scotty: Jesus fucking Christ.

Okay, fine, fair enough. I can make like it’s torturous, but it has to be done – hell, it’s why I’m here right now anyway.

What is Big Fucking Deal?

Look at any “Greatest High School Movies” list, the tributes to the late John Hughes, the various critical responses to the High School Musical franchise, or matter-of-fact titles like The Secret Life of the American Teenager and you’ll find a common thread – a search for the story that Finally Gets It Right. The best of the best, it seems, are the movies that capture what it was “really like” being a teenager, that meet the elusive but apparently attainable standard of universal relatability.

And that’s ridiculous. Not only is a story for everybody really just a story for nobody, but it’s damn near impossible to write. Going into BFD I knew the project had fundamental limitations. Chronicling life in the rural Midwest meant chronicling the lives of mostly white kids, and though there’s nothing exactly wrong with that, it certainly meant I had to drop any pretensions of universal relatability right from the beginning.

Nevertheless, I had my issues with the genre, and there were things I set out to fix, to Get Right. The foremost goal with BFD was to write the comic I always wanted to read in high school, but never did, because it hadn’t been written yet. As a teenager I was tired of stories about virginity and prom and cliques and graduation. The shit I thought was interesting about my life seemed to happen just as often in classrooms or basements or backs of cars, on weekday afternoons, in months far away from graduation.

As time went on, and I got older and further removed from my teenage years, I developed a second goal: to not get bored. You know when you’re reading the work of a bored writer. I could tell my story exactly as it happened, pure autobio, but I already know how that story goes. There’d be no surprises in writing it, and likewise no surprises in reading it. In the latter half of BFD (spoiler alert!) some of our heroes go to prom. For two pages. I had a good time at mine, as I recall, and for all I know some people’s lives have changed dramatically on their prom nights. But a bunch of kids just dancing around, having a good time? I’d fall asleep at the keyboard if that went on for more than two pages, and it wouldn’t be a good time at all. And Carl would hate drawing that.

Which brings me to another goal I developed during the project, maybe the most important goal, or at least the most tangible: don’t bore the hell out of Carl. Carl and I went to High School together, and – perhaps more crucially – have spent the subsequent years reminiscing and over-analyzing our experiences together. While the characters and situations and dialog may be mine initially, Carl’s been the first person to hear any idea I’ve had, good or bad, and he’s been right there fleshing them out with me ever since this all started.

But he’s a tougher crowd than most. I don’t say that because he’s hyper-critical (though that wouldn’t be too far off a description). I say it because Carl will have to read and re-read this shit, my shit, more than anyone else ever will. More than me, even. If I’m going to ask one of my best friends to effectively study my writing for a few fucking years, then I better make it damn worth his while. I think I have. I’ve spent plenty of hours worrying about what a reader might think of BFD, but that never gets anywhere and I won’t truly know until some stranger picks it up. But I wrote it for Carl, and I’ve got him hooked. Let’s hope everyone else has his taste. If there were only more like him…

Oh yeah, did I mention that he’s a really fucking good cartoonist? It’d be a goddamned public disservice to make this guy draw bullshit for 250 pages:

Shit, did I just implicitly call BFD a public service?

So, back to the point…what’s BFD about?

In short, Big Fucking Deal is a comic about six high school juniors living in Bluff City, MN in 2006-2007. It’s a coming-of-age story that eschews the traditional rights of passage; a story that says even the smallest moments can be a Big Fucking Deal.

Not too bad. Only took me 1,200 words to get there.

2 – EXECUTION

or Making a Big Fucking Deal

The majority of BFD was written over the course of a year I spent living in Richmond, Virginia, the year after I graduated from college. It was a good year, a great year, one of the best years…but that’s another comic (seriously, with Palmer Foley, it’s gonna be great). Which means that while Carl and I kicked around plenty of BFD in each other’s presence during the preceding few years, the first full draft of the motherfucker was completed while we were half a country apart, while I was working a full-time job washing dishes and chopping broccoli, hosting bizarre theme parties in my apartment, and making a mockumentary. So why embark on such a project?

I don’t know, I didn’t really decide to, it just happened. Like my sexuality or my recurring rabbit dreams or my love of deep-fried seafood (yes, all equally important), the compulsion to create was not a choice, or born out of any rational thinking. You wanna make a comic book about teenagers hanging out for a year? Yes! Why? Too late, I’ve already started!

I can go into the “How?” of it, though. Carl and I get asked about our process a lot, and anybody that’s asked us when we’re both present has had the good fortune of enduring something like 45 minutes of banter between a married couple that raised a comic book instead of a child. So here’s the relatively concise version (thus removing our culpability in talking your ear off should you ask us instead):

Step One: Scotty realizes his outline is bullshit. He wanders around the room, talks to his stuffed rabbits, Googles his name, drinks too much tea, has a beer to balance it out.

Step Two: Scotty eventually cranks out something that resembles a scene. The requisite characters are present, they discuss things that establish their individuality and their potential dynamic, themes are implicitly addressed, and his visual descriptions could best be described as half-assed overcompensation.

Step Three: Scotty does this throughout the script, and finishes it. He e-mails Carl.

Step Four: Carl receives the email. He reads Scotty’s work. He makes note of what he likes, and the times Scotty is asking for way too much (Scotty, that insensitive jerk, totally ignorant to the plight of the cartoonist).

Step Five: Carl and Scotty talk on the phone for hours. This consistently includes a panel-by-panel script analysis, recaps of the last episode of Community, stories of excessive spending at the comic book store, discussions of what should change in the next draft of the script, doom metal, and heaping praises on each other. Aspects of this process were dramatized in their comic “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad…” Here, though Carl is nominally the “artist,” he contributes to the crafting of the story.

Step Six: Scotty, with his sufficiently legible notes from the phone conversation, returns to the script. He is inspired by Carl’s suggestions and enthusiasm and he is focused. The scene gets tighter, retaining the necessary elements, shedding the superfluous ideas, and gaining a visual coherence. Here, though Scotty is nominally the “writer,” he contributes to the visual components of the story.

Step Seven: Carl reads it. It looks good enough to draw. He thumbnails. This will make the initial art less daunting, but also warn of potential problems.

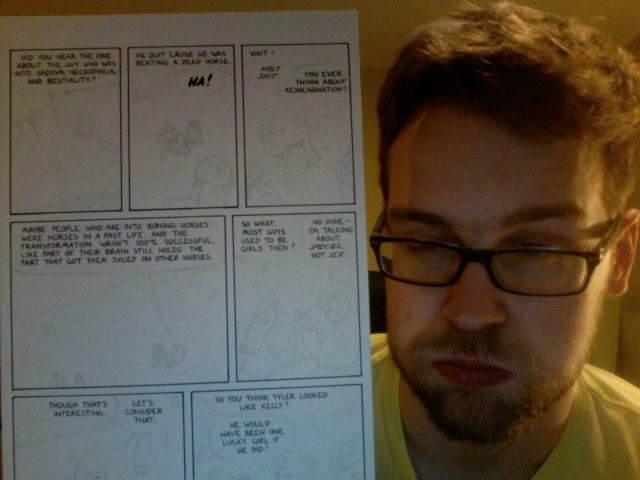

Step Eight: Carl brings the scene to life by depicting the characters as ghosts.

To him, however, it looks more like this:

Step Nine: Scotty approves, because he better. Occasionally he may notice a character’s expression not quite matching his or her dialog, and Carl makes the requisite changes. Occasionally he may notice an issue with a character’s wristbone, but he should keep that shit to himself.

Step Ten: Carl applies ink to the pencils, adding depth and dimension, making the consideration he put into composition now apparent.

He also gets to letter the dialog, which might seem wordy now, but that extended tangent about horse sex is essential to characterization and story, seriously.

Step Eleven: Carl scans the images, and uses software to render it in a clear black and white.

That’s it. A simple eleven-step process, that must be repeated hundreds of times over.